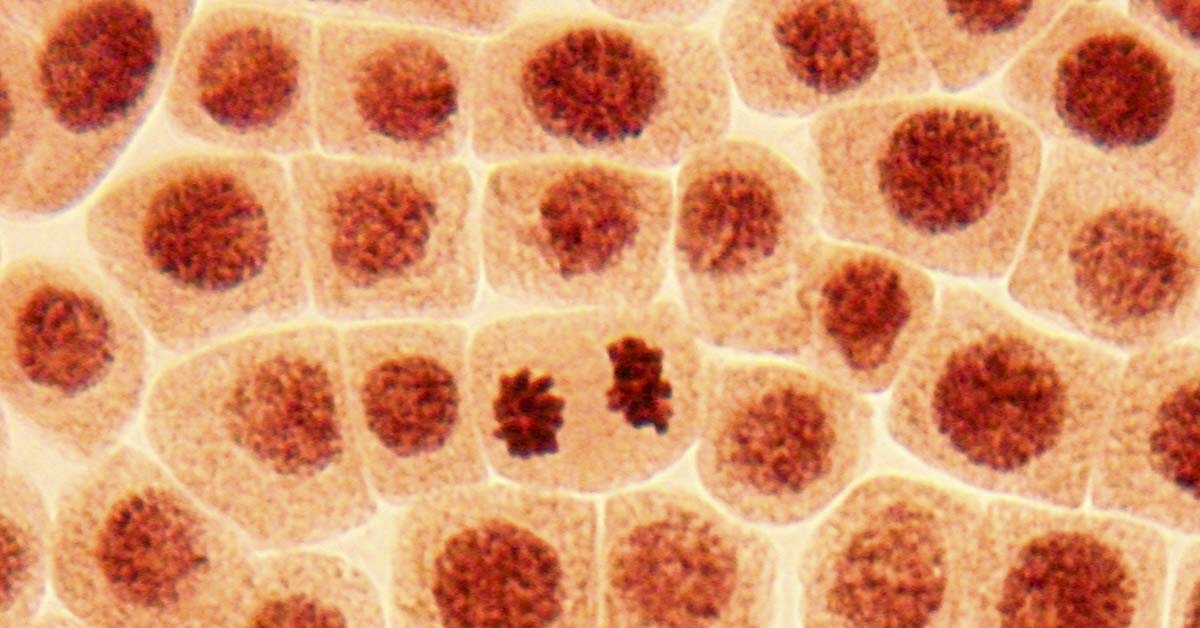

More than two decades ago, Diana Bianchi was examining a sample of a woman’s thyroid when she noticed the presence of Y chromosomes in the tissue. She realized that the woman had carried a male embryo years ago, and some of the cells had migrated beyond the womb. Thereafter, they had embedded themselves in her thyroid and other organs. These cells subsequently adapted to their environment, performing the same roles as the cells surrounding them. Amazingly, the woman’s thyroid had been remodeled by her son’s cells. So, can fetal cells stay in the mother? Well, it appears that maternal-fetal cell transfer can indeed occur, and this fascinating biological phenomenon is known as microchimerism.

How Microchimerism Works

Fetal cells cross the placenta during pregnancy and get embedded in maternal tissues, where they can remain for decades or even a lifetime. These are by no means hitchhikers, though, and integrate into organs, contributing to repair and influencing immunity. These fetal cells start to cross into maternal circulation as early as six weeks into pregnancy. Several studies have demonstrated that these cells lodge into maternal tissues, including bone marrow, lungs, liver, thyroid, brain, and skin. Furthermore, they were found to stay there for decades.

Read More: Inspiring Photo Shows The Strength Of Moms When Giving Birth

Maternal-Fetal Cell Transfer

Fetal cells have been discovered inside mothers’ brains, and some even develop into brain cells. According to studies, more than 60% of women had brain cells that carried Y chromosomes. This indicates that they were most likely from a male child they had once carried. Interestingly, there were fewer of these cells discovered in women with Alzheimer’s disease. This suggests that the cells may assist in protecting or even repairing the brain. Animal studies have also demonstrated that fetal stem cells can settle in brain tissue. Scientists continue to examine whether these cells assist in thinking, memory, or protect the brain from disorders as individuals age.

Repair vs. Autoimmunity

Microchimeric cells can speed up healing by populating injury sites and converting into tissue-specific cells, such as pancreatic islets, liver, thyroid, or skin cells. On the other hand, they can sometimes cause misdirected immunological responses. Fetal cells have been linked to maternal autoimmune disorders, including systemic sclerosis, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Sjögren’s syndrome, and lupus. These cells may mimic graft-versus-host disease, causing inflammation. Maternal health outcomes are likely determined by a delicate equilibrium of healing and immunological damage.

Read More: Sex Ed Missed This – Here’s What You Really Should’ve Been Told

Tolerance and Complications

Fetal microchimerism may help the mother’s body accept the baby throughout pregnancy. It could potentially be doing so by conditioning her immune system to adjust to the baby’s cells. This occurs, in part, due to the exchange of cells through the placenta. However, if this process is unsuccessful, it might result in complications such as preeclampsia (high blood pressure during pregnancy) or even miscarriage. One study revealed that when fetal cells do not move normally, it is associated with indications of placental dysfunction. Following delivery, cell interchange between mother and infant can continue, particularly during breastfeeding. This ongoing sharing may have an impact on both of their immune systems.

Continual Exchange During Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding allows cells to continue migrating between the mother and the infant. Breast milk contains the mother’s cells, which help the baby’s immune system develop and become stronger. Breast milk may also contain fetal or maternal cells, allowing the mother’s body to accept the baby’s cells long after birth. Animal studies demonstrate that cell exchange through breastfeeding is vital for teaching the baby’s immune system not to target specific cells. This may be helpful in later life scenarios such as organ transplants. This continuous exchange of cells establishes a long-term biological relationship between mother and child that extends far beyond nourishment.

Read More: Woman Calls For Separate Waiting Rooms for Those Experiencing Pregnancy Loss

Microchimerism and Chronic Disease

Microchimeric cells can be found in tumors and damaged tissues. Here, they could help with the healing process or even serve as immune system protectors. Fetal cells are often detected inside breast and lung cancer tumors, but researchers are still unsure whether they actually support or worsen the disease. A 2024 mouse study discovered that fetal cells in the mother’s lungs altered how the lungs responded to inflammation during pregnancy. This potentially changes how healthy the lungs are after birth. These cells may help explain why some women experience more lung difficulties after birth.

Biological Memory and Longevity

Free-floating fetal DNA rapidly vanishes after delivery, whereas microchimeric cells can remain in the mother’s body for years, if not forever. Over time, the volume of these cells normally decreases, but they can reactivate if the mother becomes ill or injured. Women with rheumatoid arthritis, for instance, regularly feel better during pregnancy. However, this improvement lasts about 15 years. This shows that these cells age with the mother. It also shows that whether they help or cause difficulties is determined by how long they have been present, where they are in the body, and what triggers may activate them.

An Evolutionary Perspective

If we look at it from an evolutionary standpoint, microchimerism seems to establish a unique bond between a mother and her child. The baby’s cells could potentially help the mother by promoting healing and even influencing her immune system. It’s like a private back-and-forth, with both the mother and child influencing each other’s bodies. However, when this balance is disrupted, issues such as autoimmune disorders may arise. Scientists believe that microchimerism is actually a normal and extremely old mechanism that continues to influence the mother’s health long after pregnancy.

The Bottom Line

Fetal-maternal microchimerism shows us that pregnancy is more than simply a brief period of sharing life; it provides a lifelong mix of cells between mother and child. The child’s cells may help heal the mother’s heart, improve her lungs, or potentially cause sickness many years later. New research is helping scientists understand how these cells work, and they may one day be used to mend damaged tissues in medicine. As we learn more, it becomes evident that pregnancy establishes a long-term cellular connection, uniting them in a complex pattern that lasts throughout life.

Read More: She Ended Her Pregnancy Based on a Paternity Test — Then Found Out the Lab Got It Wrong